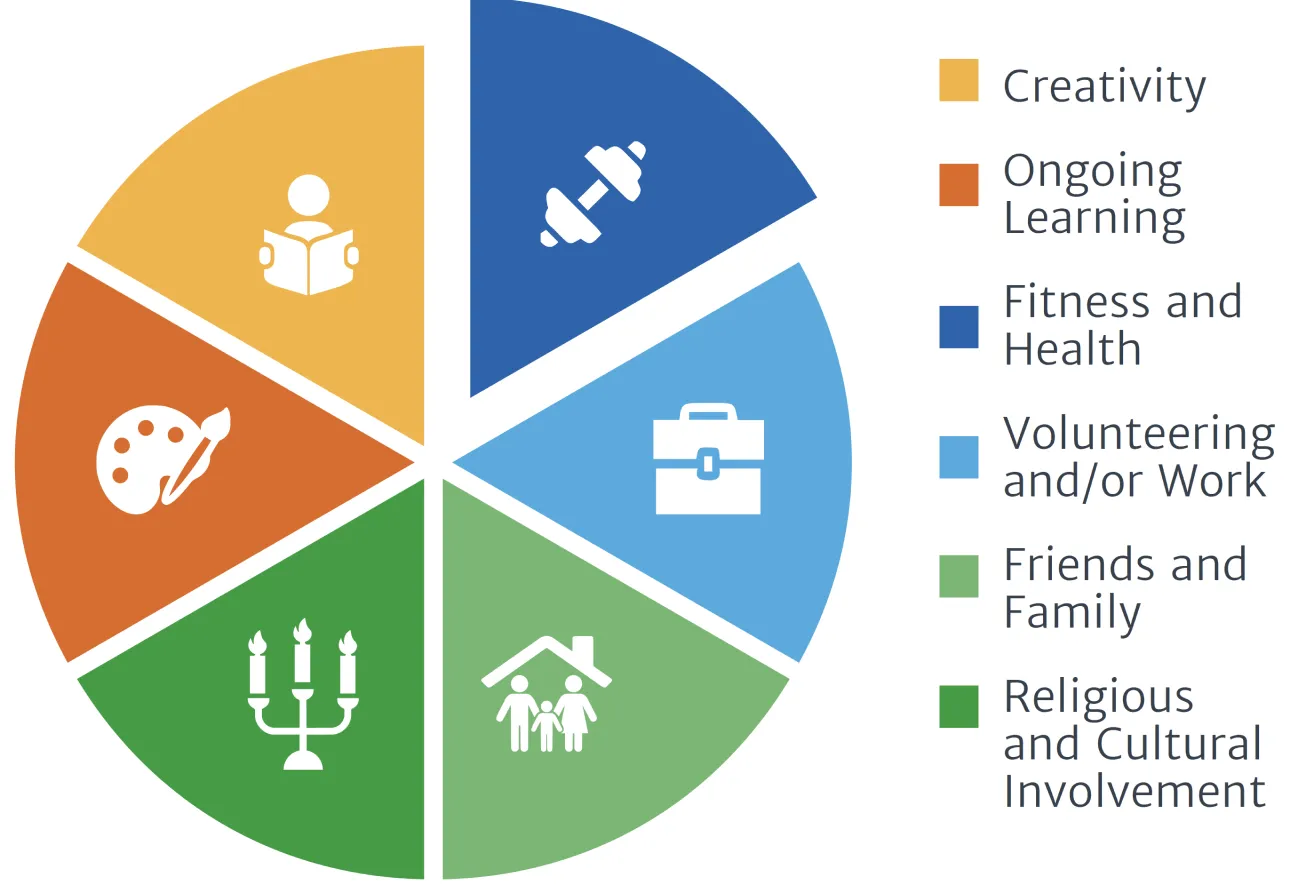

As the experts in this field often assert, people of all abilities who have a high quality of life usually fill their lives with a wide range of meaningful experiences. Below is a representation of the basic components of a good life that should be included in any “visioning” exercise.

Remember: if there is a disproportionate emphasis on one sector (“He/she has to get a job!”), it can lead to the neglect and disregard of other potentially enriching activities.

It is very important to centre the opinion and past successes of the young person with Down syndrome in any process to arrive at a vision for their life. Many families have found that a consultative process where family members of all generations, past teachers and coaches, and other significant people are consulted, can lead to “outside the box” thinking and networking.

The following are examples of activities that have contributed greatly to the post-secondary lives of young adults with Down syndrome around the province:

attending religious and cultural events, learning sacred music or rituals, contributing to the community, volunteering at events, taking Tai Chi classes

visual arts, dance, drama, fashion design and sewing, making TikToks, DJing, joining an improv group or drum circle

Special Olympics, developing cooking skills, learning to do yoga, working out, walking/running, playing golf, belonging to a bowling league

volunteering at the food bank, in a seniors’ centre, canvassing for a political party, part- or full-time employment

visiting, offering childcare, contributing eldercare, planning birthdays and holidays, following a local sports team

travelling, enrolling in classes, taking pottery classes, learning to work in watercolours, taking college or university courses

Additional Comments:

1)

Once a vision is arrived at, families should not feel pressured to support the young person to do all their preferred activities at once. Some things can wait, and people’s interests evolve! It is important to keep a record of the results of the visioning work, however, because real life can intrude and good ideas can slip away.

2)

There are other, weighty questions that may impinge upon visioning exercises for young people with Down syndrome, including the complex issues of housing, transportation and financial support. There are resources that offer guidance on these complex topics. One of the best is Safe and Secure: Six Steps to Creating a Good Life for People with Disabilities. This book was written by Al Etmanski, a founding member of the PLAN Institute for Caring Citizenship. Among other themes, it stresses the importance of families banding together to create the changes their young people require, and engaging in political action to alert government to the inclusive policies and services that are needed.

It is important to know which agencies in your area offer programmes that are appropriate for young adults with Down syndrome. The obvious first choices are the local Community Living organization, the local chapter of Special Olympics and agencies that do employment support and job coaching, but there are often numerous other organizations and opportunities that parents might not know about, when they are embarking on the transition to post-secondary life.

After studying their websites, connect with the agencies and learn how they might be able to support your child. Because it is easy to forget about programs that might indeed be helpful and appropriate for your young person with Down syndrome, it is acceptable to request a recurring annual interview, on an ongoing basis, to learn if new programmes have been launched, and to keep your young person’s needs and interests on their radar.

When your child was a secondary school student, they may have made connections with prospective employers through co-op and work placements. It is a good idea to return to those connections during the transition to post-secondary life, to learn if they may want to offer additional opportunities to your young person, or if they might have advice about further training that would benefit them.

Some families find it exhausting to survey all the possible opportunities for their young person with Down syndrome, and they would be right – it is a lot. The solution is to band together with other like-minded people who have family members who need similar supports, and to share information and insights. By assembling a database of options, they support one another and get to solutions more quickly.

Families can cooperate to share more than research and information: they can share supports. Since transportation is a real challenge in the transition to post-secondary life, families who alternate driving responsibilities to deliver their young people to programs they both attend will find the mutual assistance very helpful. Families who provide social opportunities for a group of friends with or without Down syndrome (i.e., game nights, movie excursions, group dates at a club) make a generous gift to the whole community and may find that other families reciprocate. When each family approaches post-secondary transition on their own, it can be very tiring, but sharing the responsibility is a relief for everyone involved.

It may seem too much to ask, but it is important to remember that parents can innovate and organize, too. The Down Syndrome Research Institute (DSRI) was a summer camp/school that was founded in London by Andy Loebus, the parent of a young person with Down syndrome. Nothing like DSRI has existed in Ontario before or since Andy’s initiative, which ran for 12 summers in London and also expanded to Peterborough, where it ran for 11 summers. Parent-initiated programmes are significant because they can address the real needs of families and young people with Down syndrome.